Go Back…

Theatre Spaces, part 3

A thrust theatre has audience members on three sides of the stage,

leaving one side for taller scenery. It is sometimes called "three quarter

round". The Ancient Greek and Elizabethan stages were thrust stages;

the major benefit of this style of stage is that it brings the actor into

closer proximity with the audience. Three front rows along each of three

sides of the stage means that many more audience members will be close to

the actors. On the other hand, the areas for scenery storage and the methods

of hiding scenic machinery are greatly reduced. Tall scenery (walls, backdrops)

cannot be placed anywhere except on the one side of the stage where no one

is seated. Theatrical illusion is greatly reduced on the thrust stage because

most audience members will not see a framed theatrical event but will see

both the events on the stage and across the stage to audience members seated

opposite.

the major benefit of this style of stage is that it brings the actor into

closer proximity with the audience. Three front rows along each of three

sides of the stage means that many more audience members will be close to

the actors. On the other hand, the areas for scenery storage and the methods

of hiding scenic machinery are greatly reduced. Tall scenery (walls, backdrops)

cannot be placed anywhere except on the one side of the stage where no one

is seated. Theatrical illusion is greatly reduced on the thrust stage because

most audience members will not see a framed theatrical event but will see

both the events on the stage and across the stage to audience members seated

opposite.

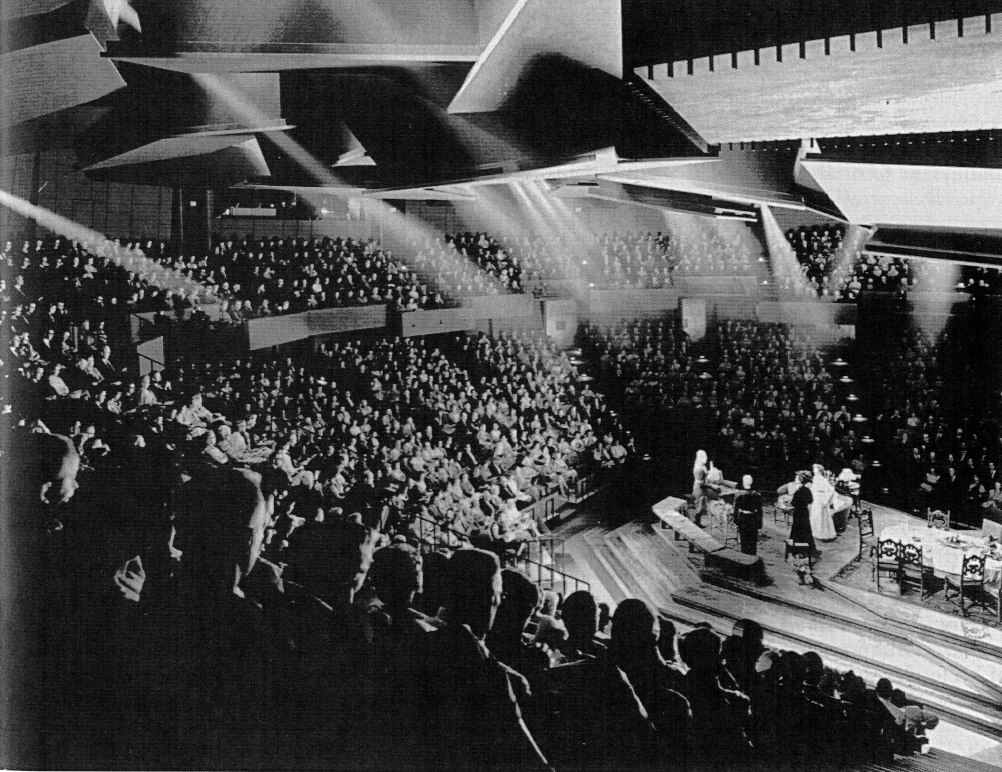

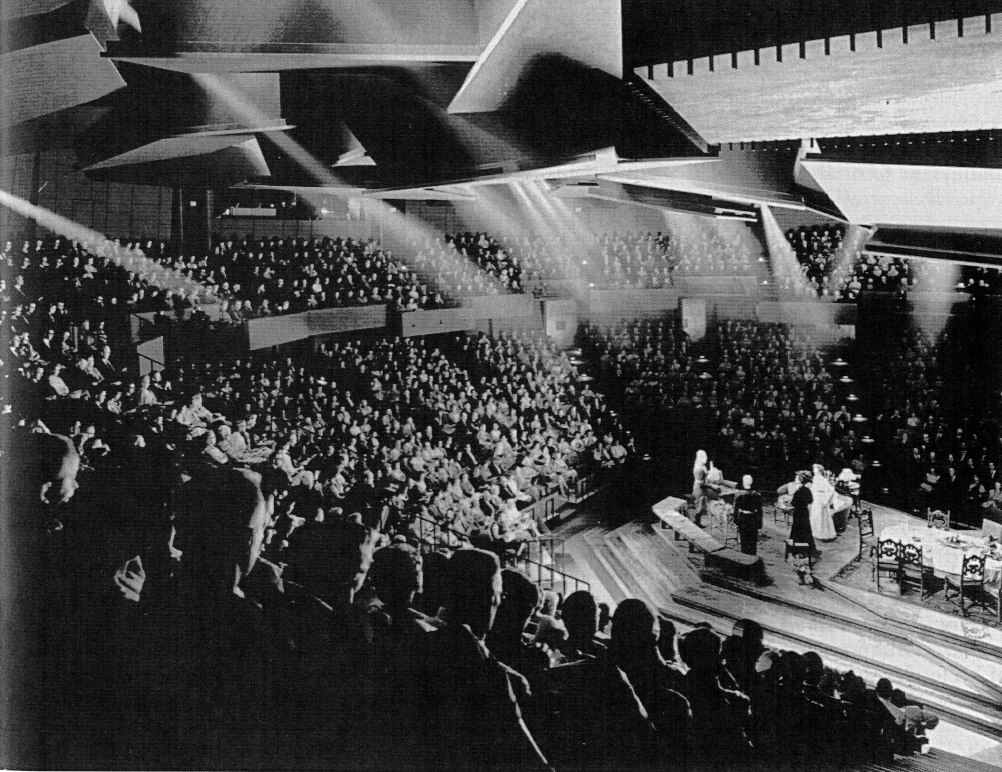

Thrust theatres have regained popularity in the twentieth century. Famous

theatres with thrust stages today include the Guthrie Theatre in Minneapolis

(see photo), the Olivier at the Royal National Theatre in London, and the

Festival Theatre in Stratford, Ontario.

Thrust theatres have regained popularity in the twentieth century. Famous

theatres with thrust stages today include the Guthrie Theatre in Minneapolis

(see photo), the Olivier at the Royal National Theatre in London, and the

Festival Theatre in Stratford, Ontario.

Most terms for parts of the proscenium stage are the same, or slightly

adapted, in a thrust theatre. For example, up and downstage are relative

to the one wall with no audience seating. Some terms do not apply; there

are rarely fly lofts or wings in a thrust theatre. An additional structure

often found is the vomitorium, a structure for performers' entrances

that originated in ancient Roman theatres. This is a ramp that begins underneath

the audience seating and leads to the downstage end of the thrust stage;

often there are two vomitoria -- one leading to each downstage corner. It

is used to bring actors and scenery on and offstage.

An arena stage has audience members seated on all sides of a square

or circular stage. It is the oldest kind of performance space, dating back

to ancient rituals probably before recorded history. No such buildings remain

today; however, the circular orchestra found in the ruins of ancient Greek

theatres point to older performance traditions before the construction of

stone theatres. An arena theatre maximizes the connection between performers

and audience, while minimizing the possibility for theatrical illusion. Many

arena theatres have been built in the second half of the twentieth century;

they include the Arena Stage in Washington D.C. and Circle in the Square

in New York City.

An arena stage has audience members seated on all sides of a square

or circular stage. It is the oldest kind of performance space, dating back

to ancient rituals probably before recorded history. No such buildings remain

today; however, the circular orchestra found in the ruins of ancient Greek

theatres point to older performance traditions before the construction of

stone theatres. An arena theatre maximizes the connection between performers

and audience, while minimizing the possibility for theatrical illusion. Many

arena theatres have been built in the second half of the twentieth century;

they include the Arena Stage in Washington D.C. and Circle in the Square

in New York City.

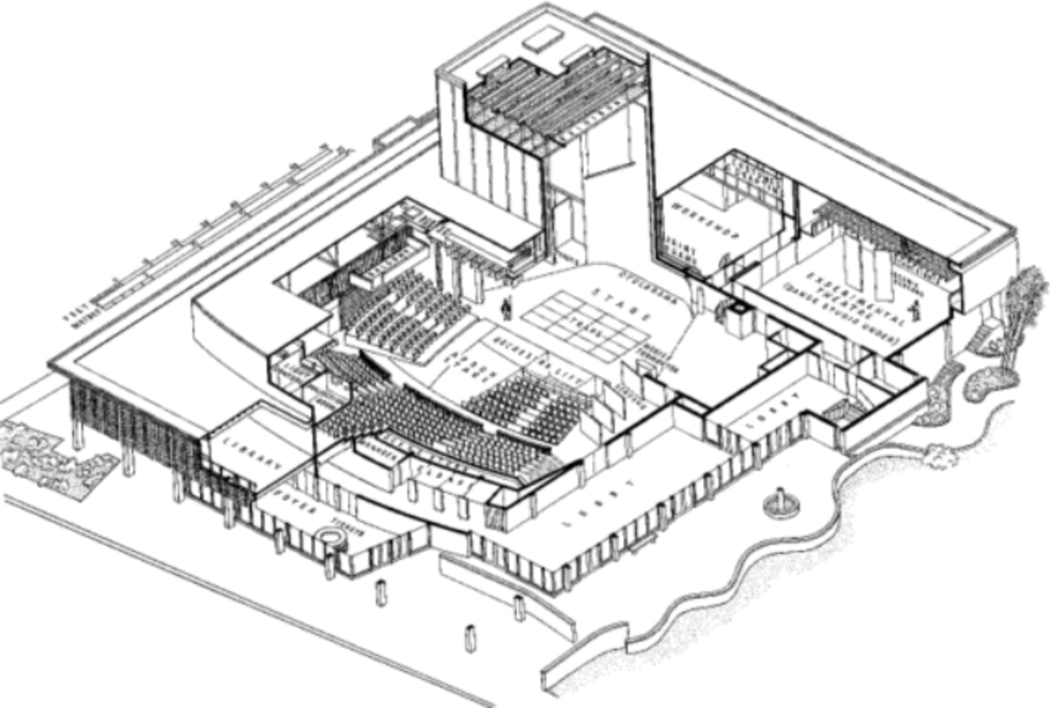

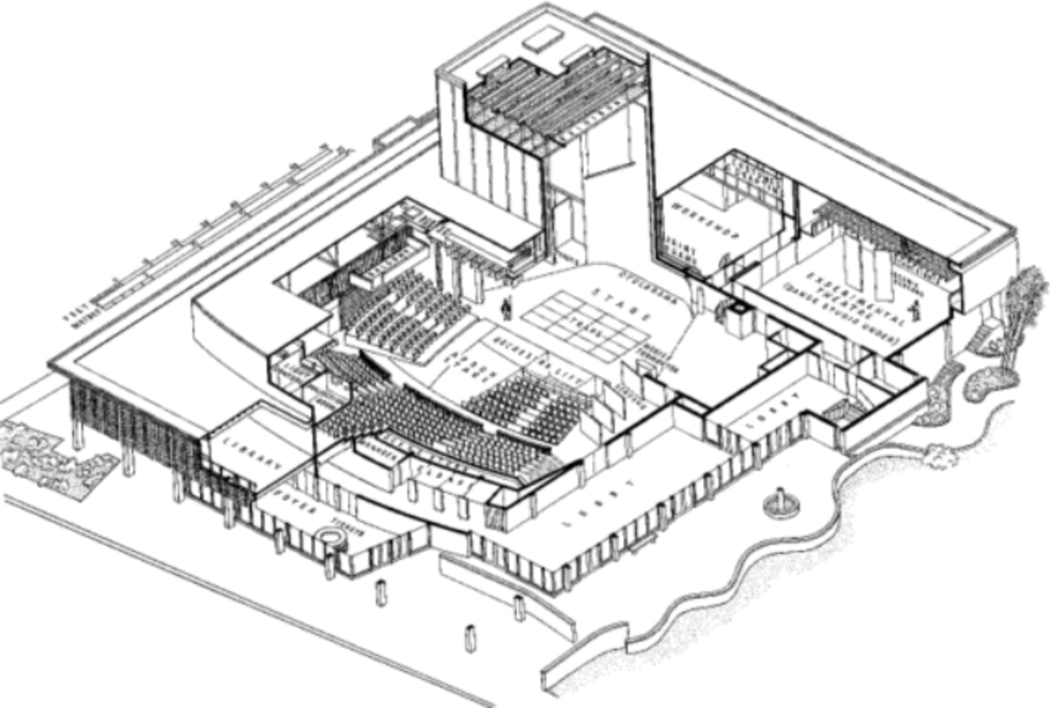

Throughout the twentieth century theatre practitioners have considered

different theatrical arrangements appropriate to different kinds of plays

or different playing styles. The German director Max Reinhardt was among

the first to advocate a theatre complex in which there are several kinds

of theatres, such as a large proscenium or thrust house and a smaller arena

stage, and to suggest that different plays require different kinds of theatres.

NewYork's Lincoln Center, London's Royal National Theatre and Barbican Center,

Atlanta's Alliance Theatre, and Chicago's Goodman Theatre are examples of

such theatre complexes. A similar twentieth century trend is to design a

flexible theatre in which the audience and stage areas can be rearranged

to form any of the three basic arrangements.  The American Repertory Theatre's Loeb Center (see photo) in Cambridge is

an example. The black box theatre (such as we have at Geneseo) is

a simple solution to the theatre artist's desire to make the space fit the

production: it is simply a room painted black, in which audience seating,

stage platforms, lighting and scenery can be placed anywhere in the room

and changed for each play.

The American Repertory Theatre's Loeb Center (see photo) in Cambridge is

an example. The black box theatre (such as we have at Geneseo) is

a simple solution to the theatre artist's desire to make the space fit the

production: it is simply a room painted black, in which audience seating,

stage platforms, lighting and scenery can be placed anywhere in the room

and changed for each play.

Continue…

Back to Blood's Course Material

home page

the major benefit of this style of stage is that it brings the actor into

closer proximity with the audience. Three front rows along each of three

sides of the stage means that many more audience members will be close to

the actors. On the other hand, the areas for scenery storage and the methods

of hiding scenic machinery are greatly reduced. Tall scenery (walls, backdrops)

cannot be placed anywhere except on the one side of the stage where no one

is seated. Theatrical illusion is greatly reduced on the thrust stage because

most audience members will not see a framed theatrical event but will see

both the events on the stage and across the stage to audience members seated

opposite.

the major benefit of this style of stage is that it brings the actor into

closer proximity with the audience. Three front rows along each of three

sides of the stage means that many more audience members will be close to

the actors. On the other hand, the areas for scenery storage and the methods

of hiding scenic machinery are greatly reduced. Tall scenery (walls, backdrops)

cannot be placed anywhere except on the one side of the stage where no one

is seated. Theatrical illusion is greatly reduced on the thrust stage because

most audience members will not see a framed theatrical event but will see

both the events on the stage and across the stage to audience members seated

opposite. Thrust theatres have regained popularity in the twentieth century. Famous

theatres with thrust stages today include the Guthrie Theatre in Minneapolis

(see photo), the Olivier at the Royal National Theatre in London, and the

Festival Theatre in Stratford, Ontario.

Thrust theatres have regained popularity in the twentieth century. Famous

theatres with thrust stages today include the Guthrie Theatre in Minneapolis

(see photo), the Olivier at the Royal National Theatre in London, and the

Festival Theatre in Stratford, Ontario. An arena stage has audience members seated on all sides of a square

or circular stage. It is the oldest kind of performance space, dating back

to ancient rituals probably before recorded history. No such buildings remain

today; however, the circular orchestra found in the ruins of ancient Greek

theatres point to older performance traditions before the construction of

stone theatres. An arena theatre maximizes the connection between performers

and audience, while minimizing the possibility for theatrical illusion. Many

arena theatres have been built in the second half of the twentieth century;

they include the Arena Stage in Washington D.C. and Circle in the Square

in New York City.

An arena stage has audience members seated on all sides of a square

or circular stage. It is the oldest kind of performance space, dating back

to ancient rituals probably before recorded history. No such buildings remain

today; however, the circular orchestra found in the ruins of ancient Greek

theatres point to older performance traditions before the construction of

stone theatres. An arena theatre maximizes the connection between performers

and audience, while minimizing the possibility for theatrical illusion. Many

arena theatres have been built in the second half of the twentieth century;

they include the Arena Stage in Washington D.C. and Circle in the Square

in New York City. The American Repertory Theatre's Loeb Center (see photo) in Cambridge is

an example. The black box theatre (such as we have at Geneseo) is

a simple solution to the theatre artist's desire to make the space fit the

production: it is simply a room painted black, in which audience seating,

stage platforms, lighting and scenery can be placed anywhere in the room

and changed for each play.

The American Repertory Theatre's Loeb Center (see photo) in Cambridge is

an example. The black box theatre (such as we have at Geneseo) is

a simple solution to the theatre artist's desire to make the space fit the

production: it is simply a room painted black, in which audience seating,

stage platforms, lighting and scenery can be placed anywhere in the room

and changed for each play.