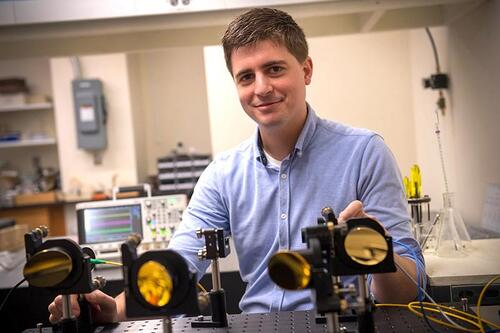

Michael Ruggiero ’12, Ph.D., assistant professor of chemistry at the University of Vermont. (Photo provided)

Michael Ruggiero ’12, an assistant professor of chemistry at the University of Vermont (UVM), was recently included in the Forbes 30 Under 30 Science 2019 list. A big fan of his alma mater, Ruggiero says Geneseo prepared him exceptionally well for an advanced career in STEM, crediting “a combination of intimate classes and a world-class faculty who has a genuine interest in students learning.”

In this Q&A, he discusses his research and the excitement he feels in the lab.

When you started college, what did you think you wanted to do?

I’ve always been interested in the natural sciences, and I originally went to Geneseo with the loose idea of becoming a physician. I quickly realized that route wasn’t for me, and I spent my sophomore and junior years trying to figure out what to do. I never thought about going for a Ph.D., and I had no idea what that career path actually looked like. That all changed once I got into the lab.

How did your undergraduate research at Geneseo help prepare you for your current work?

My research experience at Geneseo was transformative. I worked with Associate Professor Jeff Peterson, who is really passionate and who got me interested in chemistry. I was not the best undergraduate student, but Jeff took a chance on me. The excitement that he instilled is what drove me to go to grad school and ultimately what led me to UVM. I’ve based my career around the excitement I felt during my time in the lab at Geneseo, and I use Jeff’s role in my life as a guide to inspire others the way I was inspired.

Jeff had a habit of always wearing a Vineyard Vines whale belt whenever he taught. It became a bit of an inside joke –– everyone knew the whale belt. When I started at UVM, he sent me my very own whale belt, and I now wear it every day I teach in homage to him.

Jeff had a habit of always wearing a Vineyard Vines whale belt whenever he taught. It became a bit of an inside joke –– everyone knew the whale belt. When I started at UVM, he sent me my very own whale belt, and I now wear it every day I teach in homage to him.

You recently completed a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Cambridge. How did you get that position, and what did you take away from it?

My postdoctoral advisor, Professor Axel Zeitler, [a microstructure engineer in the Department of Chemical Engineering and Biotechnology,] is a big name in my field. I emailed him while I was in London for a conference during graduate school at Syracuse University and asked if we could have lunch while I was in town. That lunch sparked a few ideas, which led to a joint grant request, and a year later we were awarded a grant that funded me to go to Cambridge to work with him for three years. It was an amazing experience where I could explore all the ideas and research interests that came to mind. There was a wonderful community of really intelligent and interested people, all of whom were up for trying something new. I’m a firm believer that people can make as much of a situation as they’d like, and I took full advantage.

Forbes recognized your work for its possible implications on pharmaceuticals. Could you tell us more about that?

One major area of my research involves understanding the physical stability of pharmaceuticals, which translates to “Why does drug X have an expiration of Y months?” We look at how the atoms and molecules move around, which paints a clear picture of the mechanisms involved with drug degradation or ineffectiveness. To do these investigations, we use a combination of both experimental work (using high-powered lasers) and theoretical work (using large supercomputers). What’s amazing about this is that each year we can push the limits of our research thanks to advances in technologies. For example, calculations that I run today would never have been possible using computing technology from the day I started my Ph.D. research just six years ago.

What do you find most exciting about your research?

The most exciting thing for me is the way that we can figure out exactly why something works the way it does, down to the most fundamental of levels. It continues to amaze me how we can understand why large-scale bulk phenomena work due to effects occurring at the single atom level (such as drug degradation, more efficient solar cells, carbon-capture materials, and so on). In that sense, I think I’m somewhat of an adrenaline junkie –– I am chasing the same feeling of excitement and discovery that I first felt in the lab in Geneseo. That feeling is contagious, and I try to instill it in my students here at Vermont.